It is a great privilege to share art critic Lyle Rexer’s brilliant interview with Juan Alonso, a novelist whose work I’ve admired for years. Why this interview is being published here rather than in The Paris Review remains a question perhaps only Karma the elephant can answer (and at the moment she’s busy embracing her love interest, Juan); in lieu of explanation, let me express how deeply honoured I am to bring you Juan’s inimitable humour, turn of phrase and fascinating literary mind. Without further ado, I turn this over to Lyle and Juan. Readers, you are in for a treat.

Playing Hardball in Montevideo: an Interview with Juan Alonso

Lyle Rexer

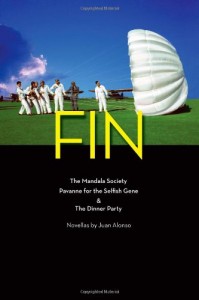

I first met Juan Alonso more than thirty years ago. I had just read his fourth novel, Althea (the Divorce of Adam and Eve), published by the Fiction Collective, and intended to review it. It seemed then (and still seems) the great novel of the 1960s I had been waiting for. That review was never published, but I did make a pilgrimage to Boston to meet him (as I recall) outside the Harvard Club. I found him everything I had not expected, including less “Hispanic,” more Bostonian, and very funny (usually writers who write funny aren’t, just as writers who write tough, can’t box). He also had founded the New Boston Review, a wonderful tabloid answer to the academic and coterie pretentiousness of its counterpart in New York. He gave me my first gig, one of the early articles in English on Thomas Bernhard. Since then I have read almost everything he has written, in various states from first drafts to finished publications. His themes are wide-ranging, from the betrayals of the Spanish civil war to the motives of Latin revolutionaries to the birth of the sexual revolution. I have also watched him, like many writers I admire, deal with a publishing industry that has given up all interest in sustaining the presence of important voices in our culture. The recent publication of his collection of three novellas, Fin (Leapyear Press) prompted me to contact him again for this extended email exchange.

NB: Juan Alonso is a professor of romance languages and literature at Tufts University. He is the author of the five novels: The Chipped Wall, The Passion of Robert Bronson, The Man with Missing Parts (with Richard Burgin), Althea (the Divorce of Adam and Eve), and Killing the Mandarin. He has also written two collections, The Chipped Wall and Other Stories and Fin. He is currently completing a novel entitled Out There.

Hola, Juan,

It’s been awhile since we talked about the completely appropriate catastrophes of Boston’s sports teams, Bruins, Celtics and especially the you-know-whos. The expression “cursed by God” comes to mind. I’ve always appreciated that the sports pages, especially relating to baseball, figure prominently in the conversation of your narrators. Can you explain this, since I have never seen you approach anything that resembles a playing field, glove, bat, ball or other moving object. Is it part of a Boston ethos?

JA: I never had my characters mention the Boston Bruins. That, Lyle, is an hallucination.

Sports pages are very specific fantasy worlds which inhabit local souls, often intensely, not only in Boston but all over the world. They are, I think, much like bars, with their particular local psychological atmospheres. They used to be a world of men, even an escape from women, especially back in the day. I needed this for The Passion of Robert Bronson and for Althea(the Divorce of Adam and Eve), which were to be the first two novels of a trilogy about America, just as I needed the narrator X.J. Muldoon’s particularly rich “townie” ethnicity. Each book took me five years to write and when I found ten years had gone past since I started the project I became alarmed and decided to go on to other work before the trilogy ate up more of my life.

As to my own unobserved athleticism (at least by you, and I hope everyone else), since you bring it up, please know I have been playing squash three times a week for the last thirty years. More recently I have moved on to playing doubles. The doubles court at the place where I play is also known, with good reason, as God’s Waiting Room.

LR: Apropos those narrators, I have been involved since I first read your work in the voices of a series of narrators, all of whom seem related – from Bronson to X. J. Muldoon to Jack (Killing the Mandarin) and finally to Fin. They speak a unique language, bemused, a little cynical but at the same time naïve, even astonished at the goings on around them. Can you tell me about the development of this persona?

JA: I can’t afford to agree with you about the similarity of my narrators. The two who tell The Chipped Wall are not like Muldoon, not like Fin the rich Canadian amateur theologian, nor like the indolent Jack, and certainly not like Rebecca, who narrates the last third of Killing the Mandarin. As a matter of fact, I have a considerable number of female narrators, starting with Celeste Riley (modeled on my studies of Mary McCarthy’s writings, autobiography included). But I will stop protesting now.

I have to agree that they all sound (and I do prefer the liveliness that the first person offers over the third person) as if they were written by me. I sometimes remind me of an Argentine radio actor from my childhood who was known as the man with a thousand voices, only they were all the same. I think of fiction writing as much like a performing art, perceiving the world through roles. The characters played are different because they are about different things, each one. If I didn’t think this and agreed about their sameness I would have to seriously consider silence, or worse. But it is a problem I have to face each time I write. I turn out to be me every damn time, always hoping that small difference will make all the difference.

As to the development of this persona (which I think is plural), all characters including narrators to me are produced by the (please excuse the expression) dialectical demands of the story. Stories, I believe, develop their own psyches, which lead the writer along. And if they don’t do so organically, I can’t continue with them.

LR: You have published with a variety of interesting presses, including my favorite, McCall’s, back in the early 1970s, and the Fiction Collective, where I first read your work. The FC was a unique enterprise and you were one of the early members, although not a founder. Can you tell me about the success or limits of the collective, was it an experiment that was good for writers or something akin to a Maoist cell, and did you have ties to the other members who published with it, like Russell Banks and Jonathan Baumbach?

JA: The Fiction Collective was indeed for some a quasi-Maoist cell, but not for all. The stern-faced Marxist Purists connected with Brooklyn College that I remember were against making good looking books because it was elitist in their view. Their future Paradise evidently promised much morality and no beauty. They knew that humor was an act of rebellion. Gravitas, that which Montesquieu called “the happiness of morons,” bless his heart, was definitely theirs. The Collective was not all that collective. Almost none were like-minded, at least with me, but it was good for some writers in that they got published. Part of the process was having a sponsor, or advisor/editor, and mine turned out to be Russell Banks, who was and is a generous man. He published there ahead of my turn. He obviously was not one to stay with them, though I do believe some, who will remain nameless, did.

LR: I think of you as having revived (if that is the right word) the novel of ideas in this country. We see this tag applied to many current novelists, including A.S. Byatt and in another vein Julian Barnes, not to mention Roberto Bolaño. In most of these cases, it is an oxymoron, where one term is at war with the other. In your case, it has always seemed a distinctive fusion of archetype and figure. The trick is to merge these with the naturalistic events of narrative, so the story does not appear programmatic. Is this how you work, consciously following a set of ideas, or is it somehow more spontaneous and organic?

JA: I did for a long time use “ideas,” sometimes fashionable ones, as moving parts, but I never proposed them nor did I agree necessarily with those characters that did. In fact, Muldoon, who suffered from idea seizures, is not necessarily “right,” and his kind of madness was in believing that things, or events, “meant.” But you are right in saying that the trick is not to appear programmatic, and I would go farther and say one should never be that kind of programmatic. But philosophic notions did spark me into writing, into making characters. This was not, however, consciously following a set of ideas, just the making of a bed, one might say, for an organic process. As in life, many literary characters turn out very differently than expected when we first meet them.

Actually, I have worked in different ways at different times and now I am working in what may be a completely organic novel, evolving out of its own “psyche,” I hope, not being pushed forward or pulled along by any army of ideas or, worse, ideologies. Its title, for whatever it is worth, is The Lost Music of the Ancient Greeks. It is true. There is now something distasteful about pushing Great Answers. Chekhov, whom I have come to love very much, was criticized in his time for not being the “great novelist” he might have been, like Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky, telling people what to think and how to live, answering the Great Questions. He simply did not have enough cheek in him to do such a thing. In that, he had the right kind of modern modesty we see in Beckett or Borges. Not to rank myself even close to them, but I would not be able to “guide” readers with ideas either. This can be left to other maniacs. One modern American (another immigrant) who would fit this mode that I can think of is Ayn Rand, but surely there are more.

LR: Your language: English. Native Spanish eschewed, though your father Amado Alonso was a distinguished historian of language in Spain. At the same time Latin America and Spain during the civil war are both subjects of your fiction. Can you talk about negotiating language and subject in your work, and your relationship to Spain and Argentina?

JA: When abroad, I am taken for American. In America I am often not. Legally I am a U.S. citizen now, a Spanish one too, through my late father, and possibly an Argentine one as well, by birth. However, I am of the opinion that one’s country is not so much a zone as it is a language. There is where I think we live. I am bilingual enough, but I live in English. That is where I reside. Not that I can’t visit and enjoy (or be embarrassed by) things Spanish or Argentine, or for that matter American, because I identify with them too. Sometimes, fortunately not often, this embarrassment can be a simultaneous, three pronged event, causing me to feel a general, zoological shame.

My living in American English was an important decision. My family arrived here when I was twelve, my father, once a Spanish exile, was now an Argentine one too. Fascism had done it to him twice. He was a considerable literary critic and philologist, and landed with one of the best jobs for a professor of Spanish literature at the time in America: the Smith Chair at Harvard University. He was soon miserable. He was a highly sociable man, but he never did learn English well enough to live in it and he suffered for it, became reduced, and certainly marginalized as he never was in Buenos Aires. I even came to believe that he died in the failed translation. This impelled me to do my best to make American English my home. By now, my relationship to Argentina and/or Spain is limited to my atavistically rooting for their national basketball teams, even when they play Americans, to return to the subject of sports.

LR: The other side of the linguistic coin then is Boston, as in, “You don’t shit me pal,” and “Life is hard but it’s harder when you’re stupid” Boston. Can you tell me about your own imaginative relations with both the city and, as you once called it, the Widener God (Harvard), hard by where you live in Cambridge? I am thinking about how Brahminism and class play out in the novels.

JA: I have no doubt that my family’s arrival in the then still Brahmin Boston (I think it no longer is) was felt by us as a cultural clash with some casualties on our side. We were a small troop of Argentine Latins (with the exception of my English mother and my Spanish father) who did not understand the local game. Harvard was a world within another world still flavored by un-egalitarian Brahmin fumes, and in a short time several of us wound up in there too, as undergraduates and even professors. It was not horrible, but different. I did not feel treated badly for my exoticism. Possibly I missed something. But it took me a bit of time, adolescent that I was, to realize that Harvard was a place with many people speaking with a Harvard (read Brahminoid?) accent who were afraid that they might be discovered as unworthy frauds. The only superior thing about many of them was their tone. T.S. Eliot was God, unquestioned. The Late George Appley was rumored to be an important novel. Harvard’s pathetic football ineptitude was considered a badge of honor, possibly proof of some sort of aristocracy. Not liking those who liked Henry James’ books made me, and many others, think we should like Hemingway’s (I changed sides on that one).

My senior year I met the historical model for Muldoon. We became friends. Ten years later, when The Chipped Wall received a wonderfully positive review in The New York Times, the historical model of Muldoon, himself born in darkest, Irish American South Boston, said to me, “Alonso, I, too, was tempted to write, but my sense of class wouldn’t permit me to work with my hands.” Another time, when I asked him where he was currently living, he grandly intoned: “I, like Jean Paul Sartre, live with my mother.”

Another night, sitting up in the now vanished Hayes Bickford’s, Harvard Square’s only all night cafeteria, I found myself at a table next to an older guy in an overcoat, scribbling very quickly in a notebook. The friend who sat with me said to him, “What are you writing?” The older guy in the overcoat smiled furtively and said, “I’m writing a book called Dirty Nice.” Another late night I saw Faulkner, sitting alone with a cup of coffee, an exquisitely tiny man, very well dressed, fiercely radiating solitude in that Brahmin Yankee world, more than a touch like a creature from another Southern planet.

LR: You mentioned that Bronson and Althea form the first two parts of what was to have been a trilogy of novels about America, which you abandoned. I wonder if you might elaborate on that. I have always felt that Killing the Mandarin, which deals with the revolutionary politics of Argentina and Uruguay, was perhaps the missing third term. If Bronson dealt with aspects of the American intellectual character and its tendency for absolutes, and Althea with the psychic currents that led to and out of the 1960s, and resulted in the transformation of sexual relations, Mandarin was about America’s dirty foreign secrets, its active participation in repression and its parallel somewhat naïve belief in liberation and freedom. The characters learn, to quote one of them, “we play hardball down here.”

JA: To think, Lyle, that maybe my abandoned trilogy about America has a concluding third novel after all! This dazzling notion has sent me scrambling back to things I have not thought about in a very long time. Your notion has merit; I can see that, even if it turns out not to be true.

The first answer lies in the Boston Irish Catholic narrator of both existing books, X. J. Muldoon, who feels he is witness to the last twilight of the American Puritan spirit, in his mind the key to American greatness, detestable as it often was. It was important to me that this vision of America and her twentieth century contortions as she emerges into her new debased Self come from him and be his “truths.” Muldoon is the one to tell it. Jack and Rebecca from Mandarin would not do as witnesses for the likes of Bronson or Althea. They were simply not made for it. For me, the narrators are the most important thing about what is narrated. Muldoon is Right Wing, by the way, as I am not. And I do not have a sentimental liking for Puritanism in general.

But, I see now that the issues in the trilogy were distinctly American, while the issues in Mandarin are about the general existential problem of not feeling real, of being forced to live out an unreal life, one not of our choosing. Rebecca, for example, feels that real life is passing her by and that she will become real only when she meets the right man. Colin Costello, the young Argentine who speaks an English no one speaks (e.g. Borges), is pretty much a conscious imitation European, humiliated by his oppressors, who hopes that his true self will become real after the Revolution (for these were the heady days of Vietnam and Fidel Castro). Only then does he think he will finally become his authentic self: the New Socialist Man, beyond exploitation, who, to quote Colin, “neither takes it nor gives it up the ass.” A utopian hope.

Here is another important difference between the abandoned American trilogy and Mandarin. No one in the trilogy is tangling deeply with the issue of killing and generally sinning, one might say, practicing torture included, for the sake of human rights. This is something that troubles Colin Costello, the novel’s revolutionist, very much. Making a revolution, to borrow from Napoleon, requires busting a lot of eggs.

As to the novel’s general politics, American Jack, the first narrator (the second is Rebecca) is more or less neutral, or at least no utopian. My personal opinion is not that America is especially wicked with its dirty dealings abroad, but that all those that can, will. States have the moral range of lobsters. I expect that all societies in our fallen world are most probably unjust and oppressive, but some less so than others. It is, of course, important to calibrate.

LR: Your work has been compared to Borges’, a connection I don’t quite see, but you do have a sort of familial near connection to the writer. I seem to recall that your mother at one point was solicited to be a date for him, but his rather unsavory social reputation warned her off.

JA: It was no date with Borges but something much worse: matrimony, which his mother, Leonor, was proposing for Georgie, as he was called, because she was worried about his being taken care of after her death. My mother refused, telling me that this was a bleak and lonely prospect, charged for the most part with keeping the pigeons off the monument.

As for my work, I don’t see it as comparable to Borges either. Maybe whoever said that was trying to be kind about (please excuse) “intellectual” fiction. Borges takes ideas and disguises these ideas as characters, but they never really come close to being like humans. That may have been part of my mother’s objection, a certain famous chilly lack of humanity. For me, the most important justification for fiction is the exploration and presentation of people as convincingly alive, in a word: psychology. Not medical though. And, of course it must be entertaining, or lose the right to exist. I even like it to be, among other things, funny, even in the teeth of what is called “reality”, or what our traditions called The Creation, or what Camus airily dubbed The Absurd.I guess one can see how it has become a word often brought up before us as a suspect manacled by quotation marks.

LR: In the recent short novel The Mandala Society and especially in the new novel in progress, Out There, which deals with the lure of the desert as a place of enlightenment, you explicitly take up the theme of spirituality. This is a loaded subject in America, where we prefer an all-or-nothing relationship with our deities.

JA: Yes, I take up this subject, but I am not selling any brand. I consider myself spiritual, but not religious. Spiritual to me is the opposite of materialist, something reductive of everything to matter. Spirit or psyche is what I write about. If matter has no psyche, no spirit, it is simply dead. I think I am trying to say modestly that I write about living and life, with all its curiosities, including relationships of many kinds. Where does this come from in my case? I don’t know, maybe I can’t know, but I certainly know what dead is, and it is not interesting.

LR: Finally, maybe, a question about the Future of the Novel, which used to be such a popular topic 30 years ago. Now people just call it “fiction.” Your novels exemplify the idea for me that fiction is a cognitive form, changing how we see and know the world. It is also a form of entertainment. Can these coexist or have we already seen their divorce, both to wither separately?

JA: The thing as we know it, the realist novel, descended from the 19th century, will pass away. When Balzac was very young, the novel genre was a low thing indeed. Trash. At the time, if you had aspirations as a serious narrative writer you were to compose epic poems in Alexandrine verses. The status of the modern novel I do believe has been sinking again, successfully and bountifully to trash once more, deeply loved trash, of course. But I do not see humanity living without stories which are also, as you say, cognitive forms, helping us to see life, though the stories will no doubt be told differently than they are now.

I have often wondered if fiction, this ironic and long-surviving tradition of stories we know to be false as a way to truth does not at least partly come out of necessity, since we humans must spend so much of our life’s energies dissimulating, to others and to ourselves, and wisely so. Because, as the mean old Latin saying goes, or went: veritas odium parit, which means: truth breeds hatred. Many truths are a lot easier to contemplate when eventually seen surfacing as a reflection in fiction’s mirror, and experienced ‘there.’ Not ‘here,’ please. But at least experienced somewhere. As such, I see fiction as enriching consciousness, and therefore important to life, therefore durable and enduring.

Lyle,

Re-reading these answers, I have to tell you, has been a peculiar experience. As they talk to me I begin to feel as if maybe I have put myself in danger of turning into a literary character myself, a creature of ink that I am looking at from the outside and don’t really know. A tougher bird than I am.

Bestos,

Juan

Lyle Rexer is a writer, critic and curator. He is the author of numerous books and articles and writes a regular column for Photograph magazine. He teaches at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan.